State-of-the-art analysis, best practices identification, and cost-benefit evaluation

RA2 expands the analytical lens through a systematic review of academic literature and existing best practices. This "Understanding-Evaluating" phase establishes the normative framework for the project, identifying key performance indicators and estimating the costs and benefits of archetypal Circular Economy interventions. Building on the empirical foundation of RA1, this activity provides an in-depth desk research using a multidimensional and integrative approach. The analysis covers technological-innovative, environmental, economic, and socio-relational dimensions to construct the most suitable CE model ("circular scenario") applicable to Historical Small Towns.

Duration: Year 1 — Second Semester

Status: Completed

Lead: RU1 — University of Messina (with RU2 contribution)

Definition of current Historical Small Town concept and types, establishing the theoretical foundation for understanding Italian borghi within contemporary sustainability discourse.

Analysis of methods and tools for urban sustainability assessment, with focus on Urban Metabolism (UM) and Urban Symbiosis (US) approaches applicable to historical contexts.

Identification of main approaches, methods, and related indicators for measuring circularity and sustainability.

Systematic review of literature on actors involved (citizens, companies, governments) in relation to circular production and consumption issues within HST contexts.

Identification of national and international CE best practices from comparable contexts demonstrating successful circular economy implementation.

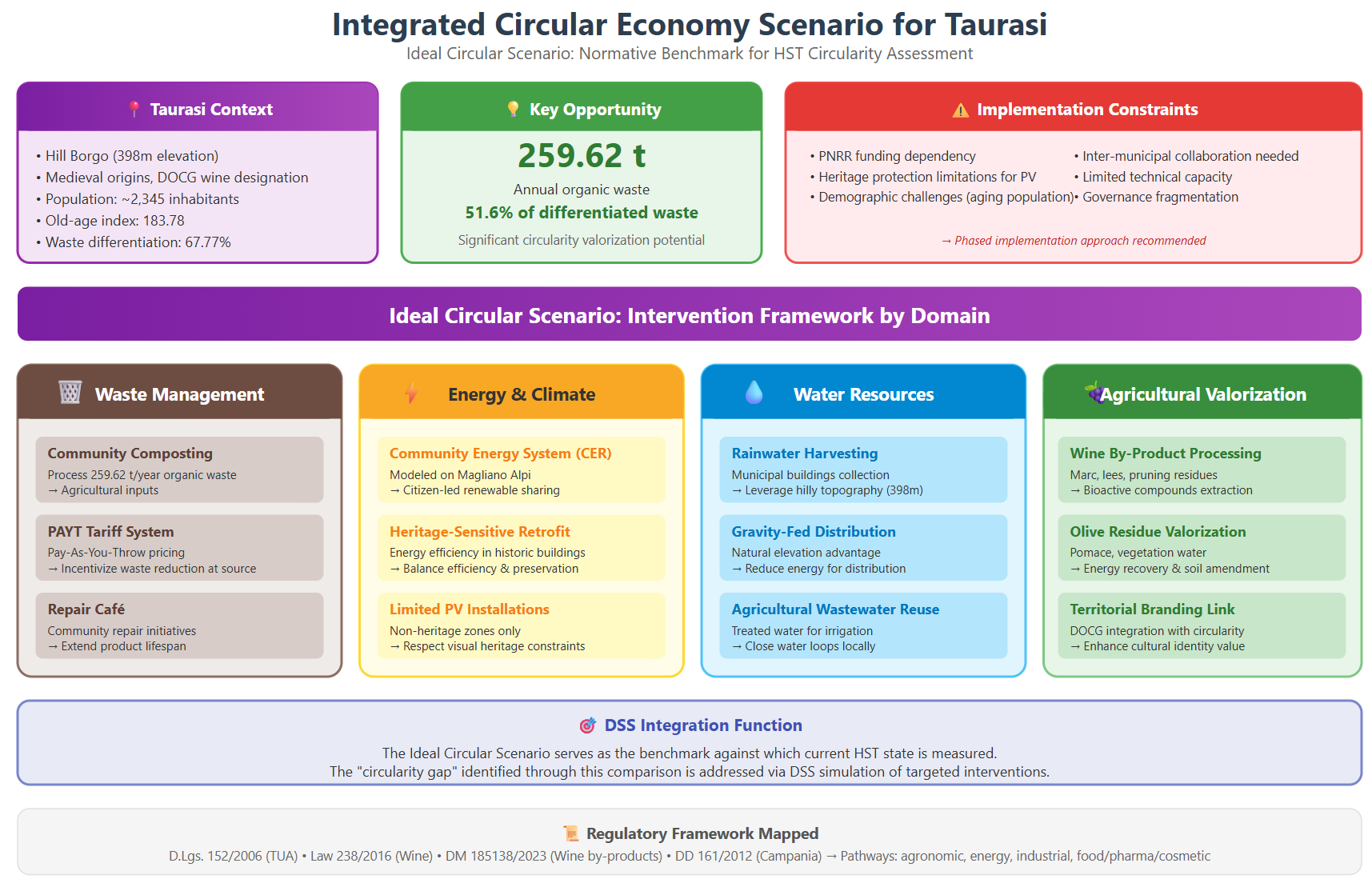

Definition of potential scenarios that can improve the "circularity potential" of the context, exploiting its resilience and regenerative capacity.

Calculation of average costs and benefits from the implementation of each intervention on the reference HST (Borgo di Taurasi).

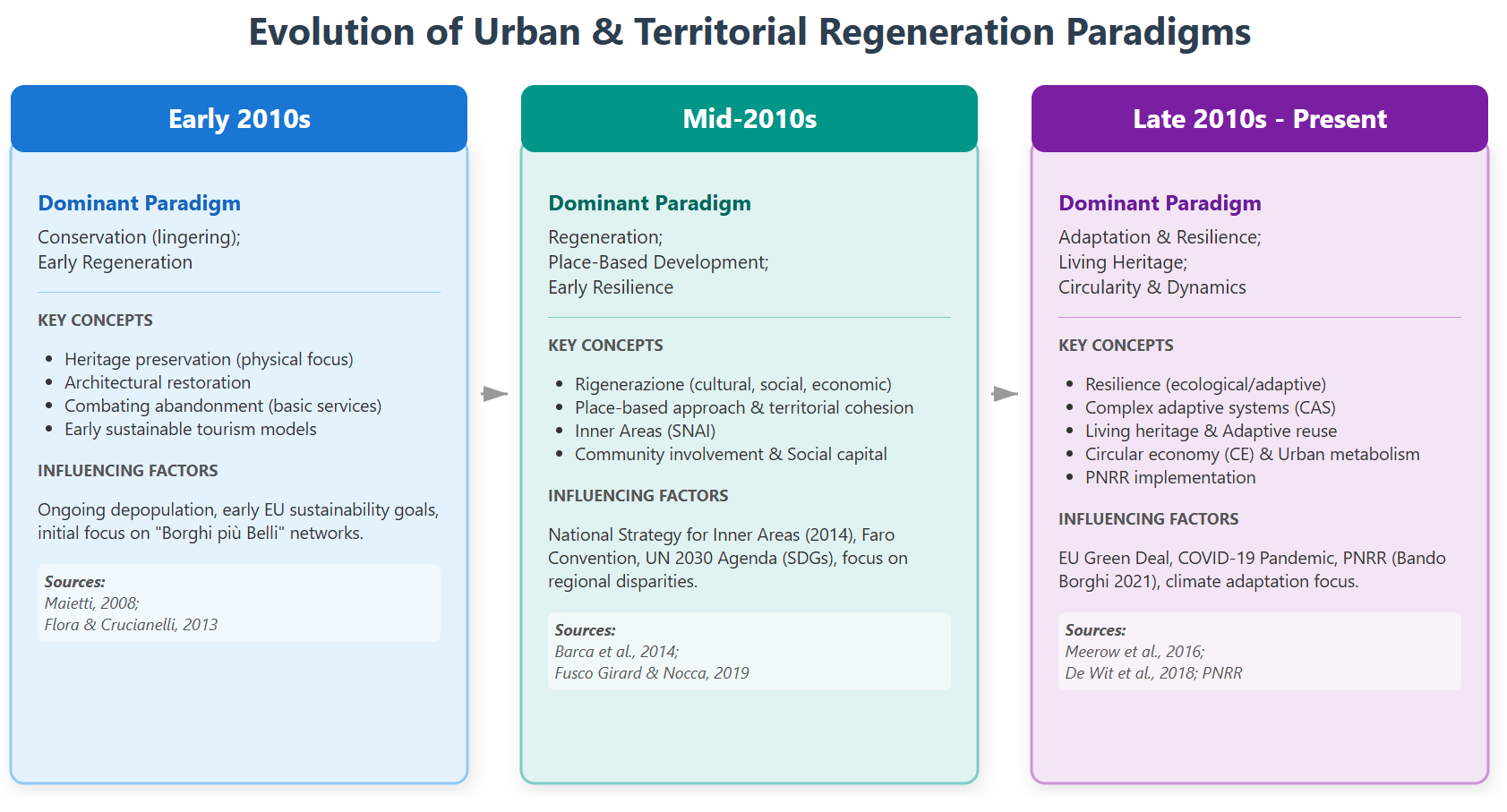

The research traced the conceptual evolution of HSTs over the past 15 years, identifying three distinct periods: the early 2010s conservation paradigm focused on physical preservation, the mid-2010s shift toward regeneration and place-based approaches (exemplified by Italy's SNAI), and the late 2010s emergence of dynamic conceptualizations emphasizing adaptation, resilience, and circular economy principles. Six key theoretical frameworks were identified for understanding HSTs as complex systems: Socio-Ecological Systems (SES), Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS), Resilience Theory, Living Heritage, Place-Based Theory, Network Theory and Circular Economy/UM. This analysis demonstrates a fundamental shift from viewing HSTs as static heritage objects toward recognizing them as dynamic systems capable of adaptation while maintaining historical continuity.

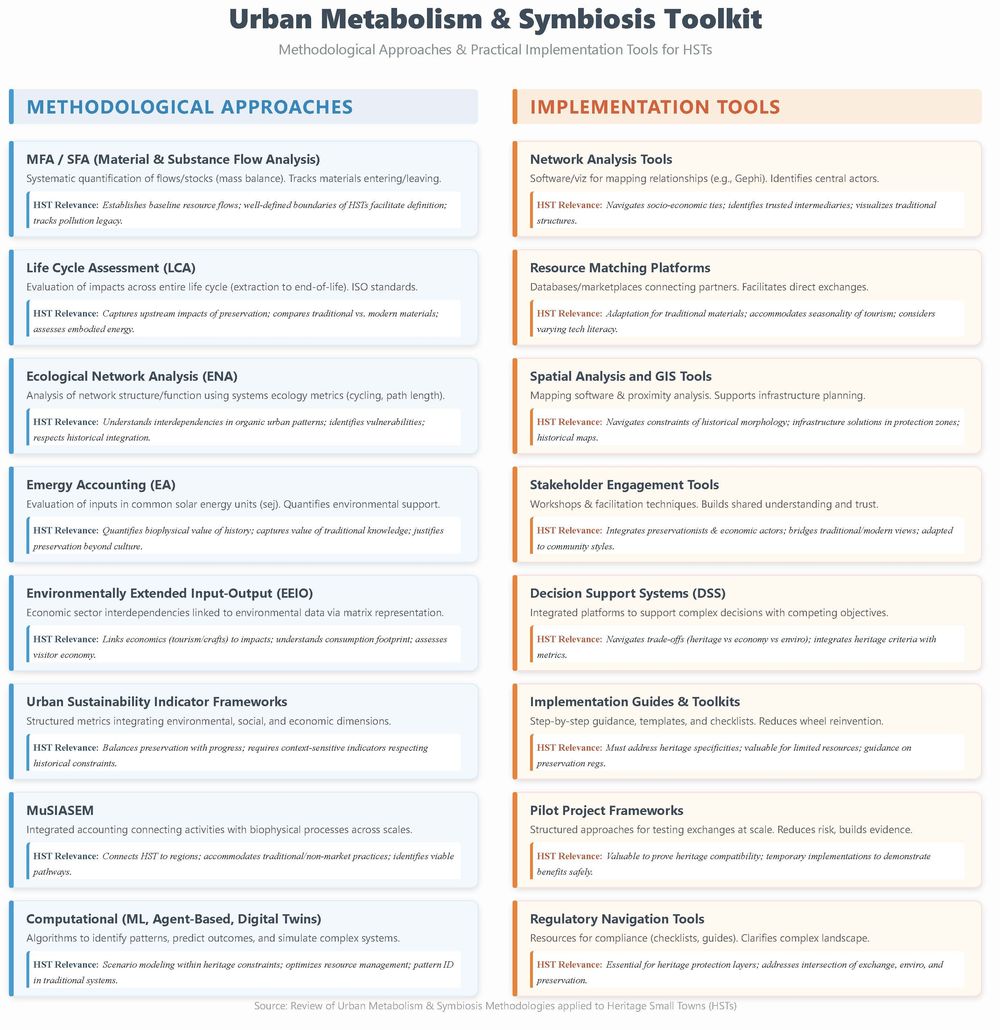

The systematic review identified comprehensive methodological approaches for Urban Metabolism analysis including Material Flow Analysis (MFA), Substance Flow Analysis (SFA), Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Ecological Network Analysis (ENA), Emergy Accounting (EA), Environmentally Extended Input-Output (EEIO), Urban Sustainability Indicators Framework, MuSIASEM, and computational methods such as Machine Learning and Agent-Based Modeling. For Urban Symbiosis implementation, practical tools were catalogued including Network Analysis platforms (Gephi, NodeXL), Resource Matching platforms, GIS-based Spatial Analysis, Stakeholder Engagement and facilitation tools, and Decision Support Systems. The analysis highlighted specific adaptation requirements for HST contexts, addressing challenges of data fragmentation, reduced scale, and heritage preservation constraints.

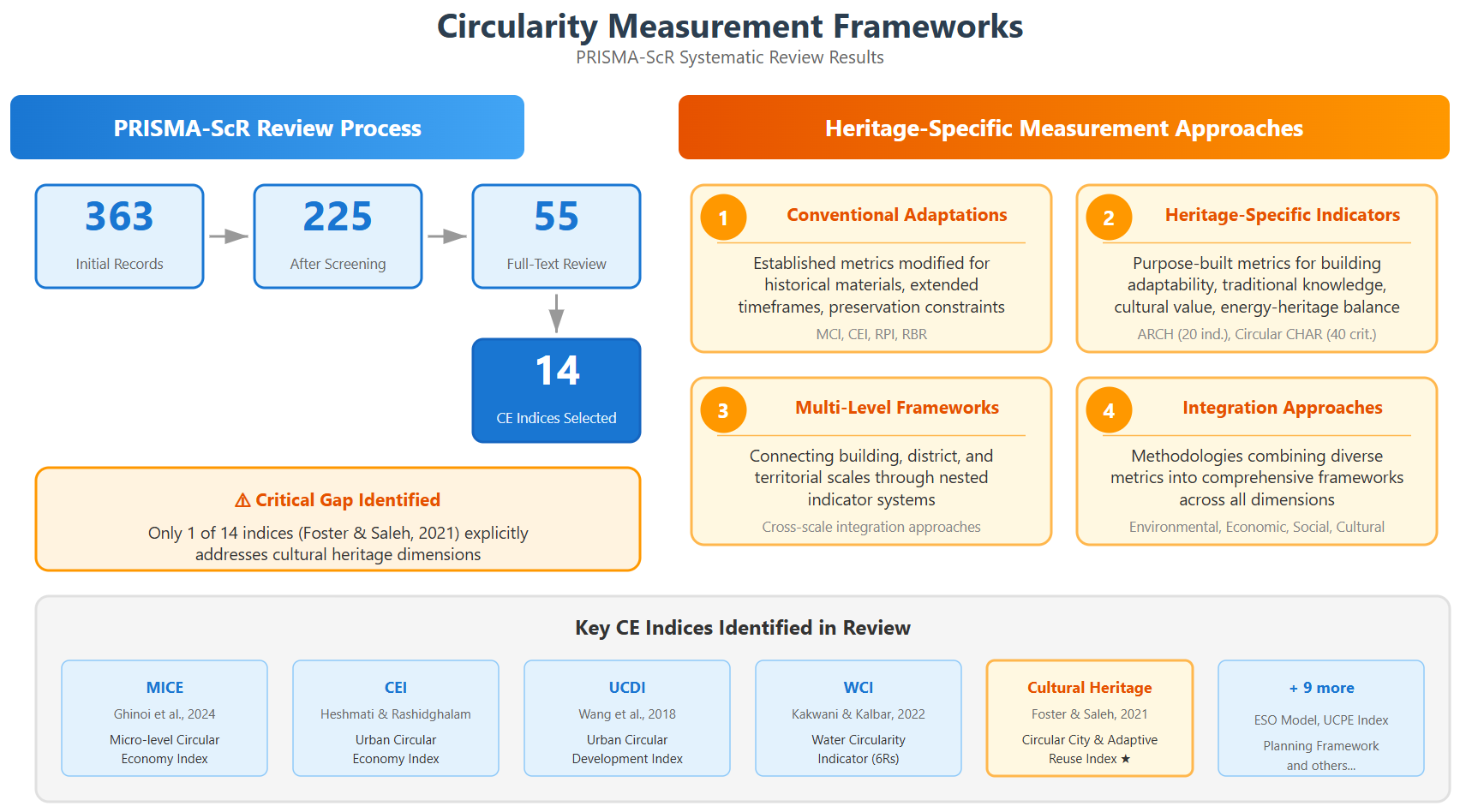

A PRISMA-ScR systematic review identified 14 circular economy indices for micro-meso level assessment. Key frameworks identified include MICE, CEI, UCDI, WCI, and the Cultural Heritage Index. A critical finding revealed that only 1 of 14 indices (Foster & Saleh, 2021) explicitly addresses cultural heritage dimensions, confirming a significant gap in mainstream CE measurement. The complementary heritage-focused review addressed this gap by identifying four categories of measurement approaches specifically designed for or adaptable to historical contexts. First, adaptations of conventional indicators uncover how established circularity metrics can be modified to accommodate historical materials, extended timeframes, and preservation constraints. Second, heritage-specific indicators provide purpose-built metrics addressing building adaptability, traditional knowledge continuity, cultural value retention, and energy-heritage balance. Third, multi-level measurement frameworks connect building, district, and territorial scales through nested indicator systems. Fourth, integration approaches offer methodologies for combining diverse metrics into comprehensive assessment frameworks that address environmental, economic, social, and cultural dimensions simultaneously.

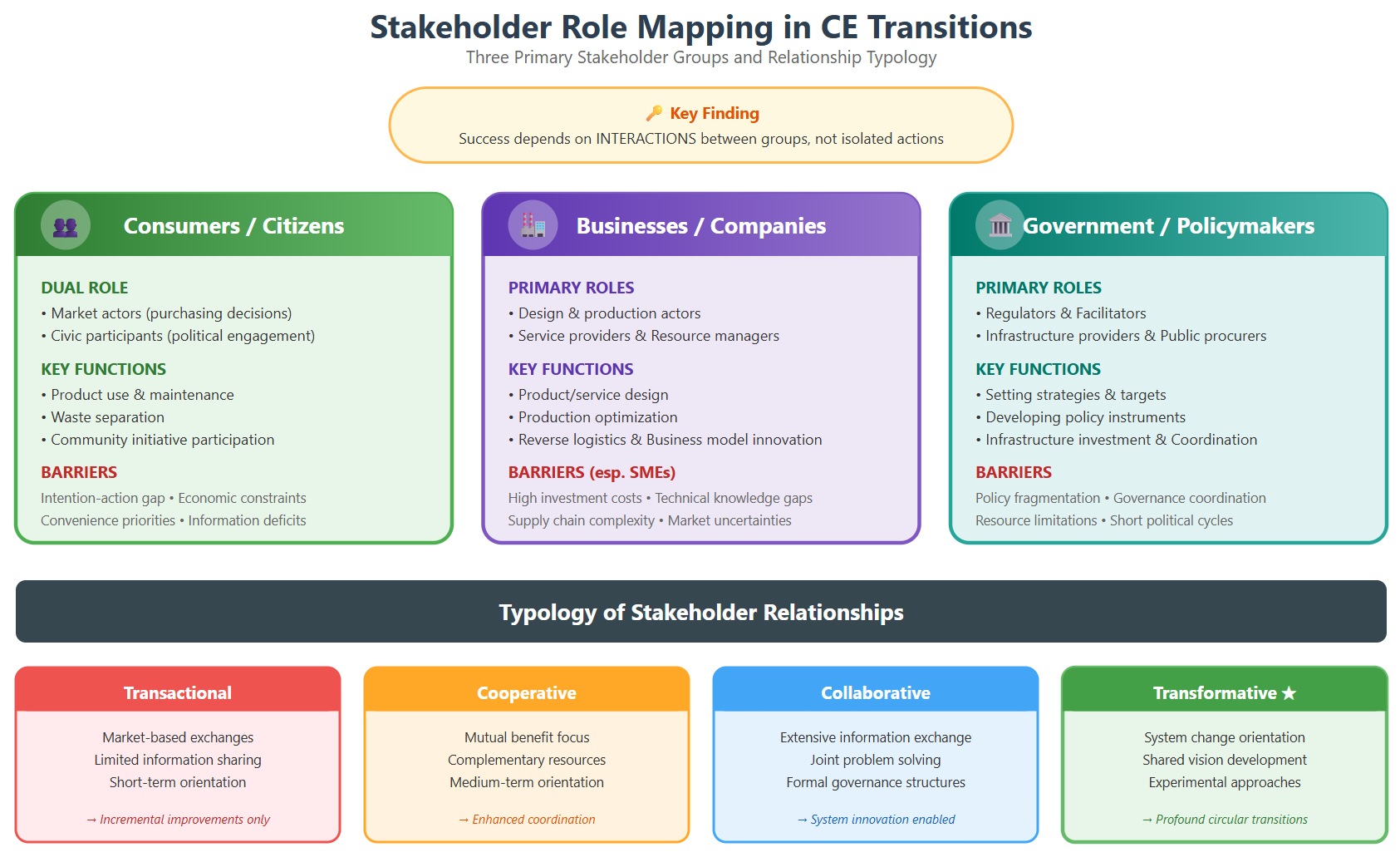

The systematic review examined three primary stakeholder groups in circular economy transitions. Consumers/Citizens operate in a dual role as market actors and civic participants, facing barriers including the intention-action gap, economic constraints, and convenience priorities. Businesses/Companies fulfill essential functions in design, production, and resource management, with SMEs facing distinctive barriers regarding technical capacity and financial resources. Government/Policymakers establish framework conditions through regulatory, economic, and infrastructural interventions, with policy fragmentation identified as a persistent challenge. A typology of stakeholder relationships was developed distinguishing transactional, cooperative, collaborative, and transformative configurations, with the key finding that successful CE implementation depends fundamentally on interaction patterns between groups rather than isolated actions.

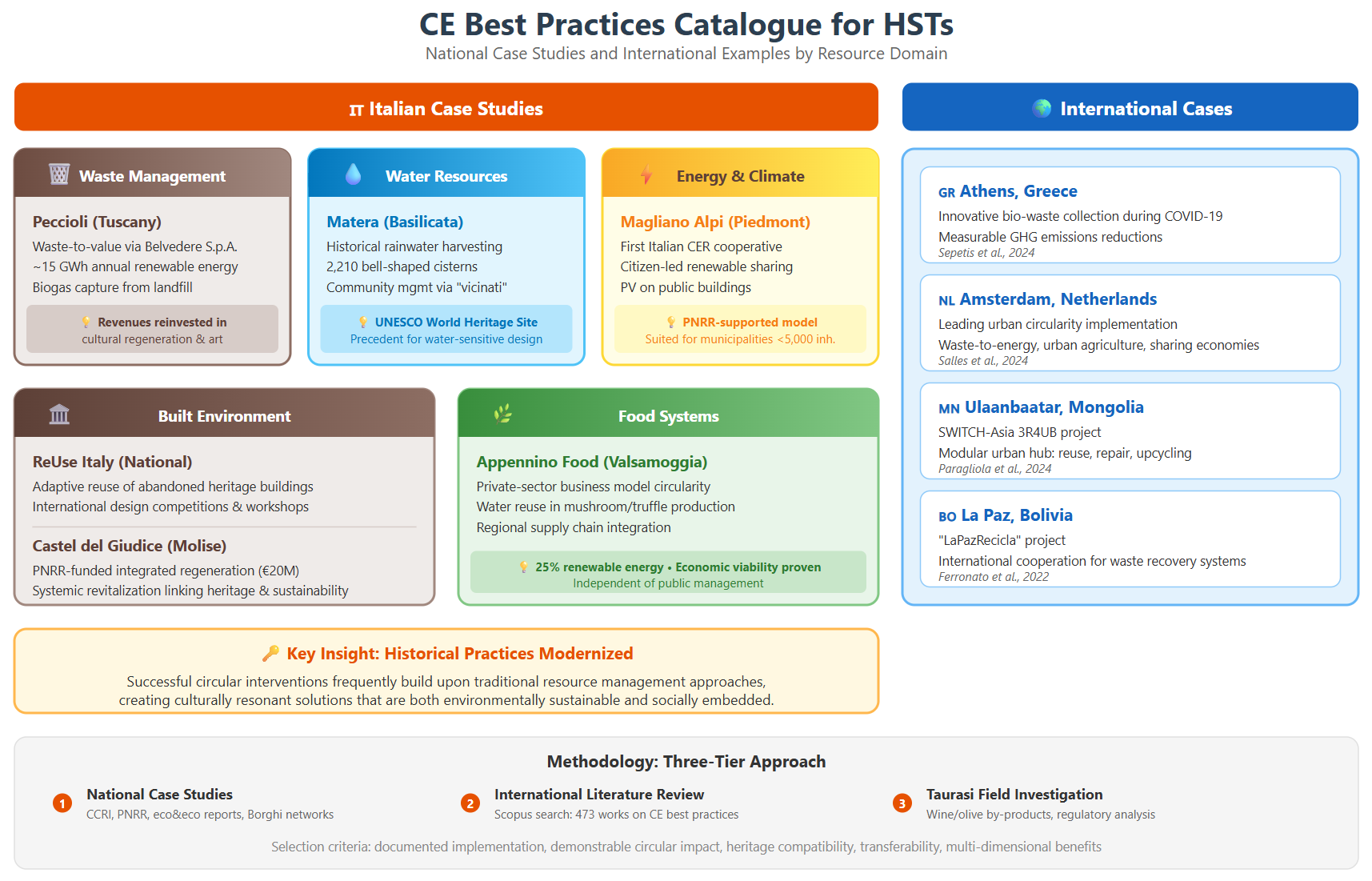

The research compiled transferable best practices from comparable Italian and European contexts. Peccioli (Tuscany) demonstrates waste-to-value governance transforming a landfill into ~15 GWh annual renewable energy with revenues reinvested in cultural regeneration. Venice provides a model for heritage-adapted waste collection achieving high separate collection rates despite severe physical constraints. Magliano Alpi (Piedmont) established Italy's first Community Energy cooperative (CER) with citizen-led renewable energy sharing from public buildings. Matera offers historical precedent through its sophisticated ancient rainwater harvesting system of 2,210 cisterns. For Taurasi specifically, opportunities were identified in wine and olive by-product valorization, with regulatory pathways mapped for agronomic, energy, and industrial applications of production residues.

The research compiled transferable best practices through national case study analysis and international literature review. Among Italian cases organized by resource domain: Peccioli (Tuscany) demonstrates waste-to-value governance through Belvedere S.p.A., transforming a landfill into ~15 GWh annual renewable energy with revenues reinvested in cultural regeneration; Matera's historical system of 2,210 bell-shaped cisterns with neighborhood management via "vicinati" serves as precedent for water-sensitive design; Magliano Alpi's Community Energy cooperative (CER) offers a PNRR-supported model for small municipalities; ReUse Italy promotes adaptive reuse of abandoned heritage buildings through international design competitions; Castel del Giudice (Molise) exemplifies PNRR-funded integrated regeneration (€20M); and Appennino Food (Valsamoggia) demonstrates private-sector circularity with water reuse and 25% renewable energy. International cases complement this catalogue: Athens developed an innovative bio-waste collection model during COVID-19 with measurable emissions reductions; Amsterdam serves as a leading example implementing waste-to-energy, urban agriculture, and sharing economies; Ulaanbaatar's SWITCH-Asia 3R4UB project created a modular urban hub fostering reuse, repair, and upcycling; and La Paz's "LaPazRecicla" project illustrates how international cooperation can catalyze waste recovery systems in developing contexts.

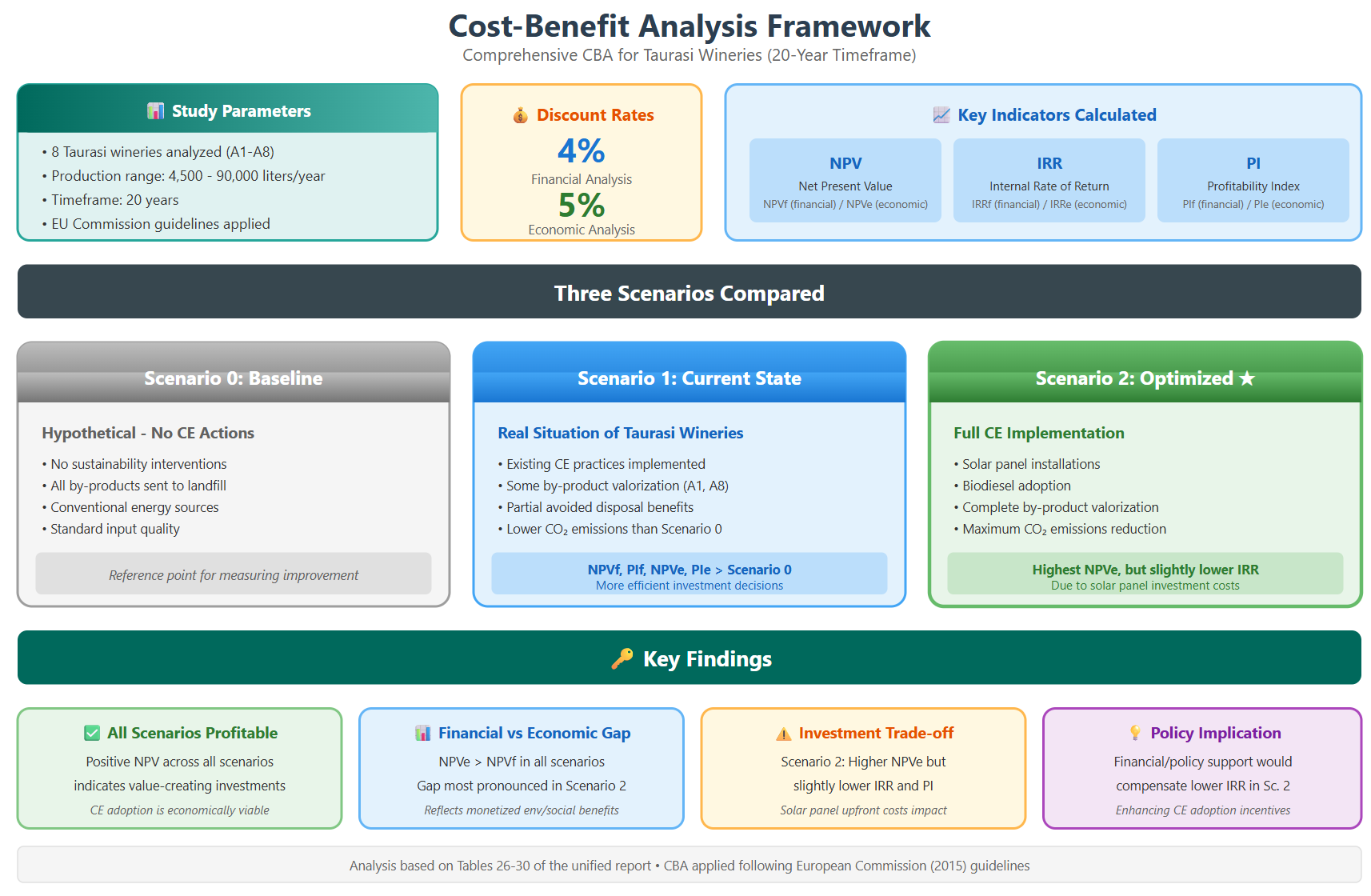

comprehensive Cost-Benefit Analysis was conducted for eight Taurasi wineries (production ranging 4,500-90,000 liters annually) across a 20-year timeframe comparing three scenarios: Scenario 0 (baseline without CE actions), Scenario 1 (current situation), and Scenario 2 (optimized with solar panels, biodiesel, and complete by-product valorization). Financial indicators (NPVf, IRRf, PIf) and economic indicators (NPVe, IRRe, PIe) were calculated following European Commission guidelines with 4% financial and 5% economic discount rates. All scenarios showed positive NPV indicating profitable investments. Scenario 2 demonstrated higher economic NPV but slightly lower IRR due to solar panel investment costs. The gap between financial and economic indicators proved most pronounced in Scenario 2, reflecting monetized environmental and social benefits from avoided CO₂ emissions and by-product valorization.